The morning of Friday May 10th was a brisk 9°C. The sunrise was not until 5:42am, however, we aimed to be on base for well before that, so we all piled into the truck at 5:00am. The prairie stretched on for miles as we drove past on desolate roads passing idyllic farmsteads and massive industrial complexes for oil and bit-coin mining.

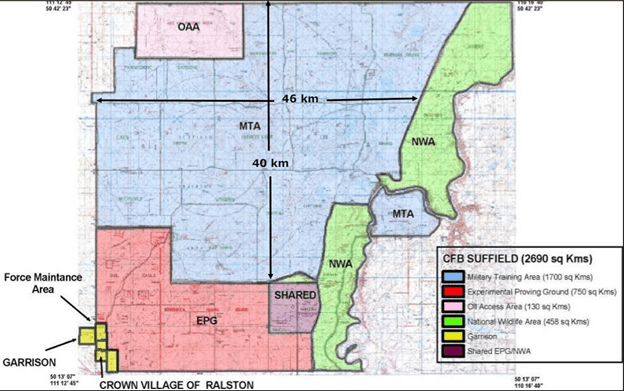

We hadn’t gotten a chance to visit the National Wildlife Area (NWA) on the Suffield Forces Base the previous day after our in-brief due to the massive amounts of rain that fell while I drove through Manitoba and Saskatchewan, making the dirt roads that create a large interlocking grid over the base more of a hazard than anything else.

CFB Suffield – the largest military training ground in Canada established, is a large plot of protected land totalling 2,700 square kilometres. It’s hay day arose in World War 2 when the British lost their chemical warfare training facility in French Algeria to Nazi Germany after the fall of France and Experimental Station Suffield was born in June of 1941.

After WW2, British forces continued to utilize a good portion of the northern area of Suffield for their own infantry training which continued until 2024, when I hear, that Britain has decided to pull their troops, essentially removing an integral purpose of the Base’s massive land mass. I am not sure the exact specifics.

In 2003, 458 square kilometres of ‘untouched’ prairie grassland along the South Saskatchewan River were designated as the Suffield National Wildlife Area. I say ‘untouched’ because it was definitely touched. Exploded even. Yet, undisturbed by industrial agriculture, leaving the land as a very important refuge for many species at risk that are unfairly targeted by the effects of agriculture across the prairies.

FYI: Due to the restrictions of the Base, and safety of the species we work around and with, I have to be pretty vague in my descriptions and photos especially including locations!

Arriving at a large metal gate, joined together by barbed wire and wooden post fences that stretched far into either direction, we radioed Range Control to let them know our destination on the grid system the Base uses, including our exact route down to which cardinal direction on which roads in specific sequence.

After being cleared, we trundled our way down a dirt road towards our first study site – Six North.

***

The sun rose over the prairie, shining a golden hue on the dewy grass and nodding onions not yet in bloom. The low-lying hills rolled on far into the distance, with a gnarled hunched over tree the only sign of plant life over 6 inches tall. All around us were the choruses of songbirds I had never heard before, yet I couldn’t see a single owner of any of the voices. It felt like someone was playing a prank almost.

Six North is hillier than our sister site, Six South, but the grass and other plant life such as the wild Alberta rose bushes, nodding onions, and sparse clumps of crested wheat grass are much lower to the ground. Scattered all around Six North are also the remains of the grazing cattle that are brought in semi-annually to keep the grasses low, and the ecosystem healthy. Without bison, the grasslands of Suffield required a grazing herbivore to keep everything in check, and the local ranchers are more than happy to supply, I suppose.

Six South, flatter with taller grasses, is pocketed with craters of varying sizes. It remains scarred of its previous use decades ago as an experimental weapons training ground and is also the site where the most UXOs (Unexploded Explosive Ordnance – bombs that did not detonate as intended) have been found out of the two. There was a whole section of our in-brief about these long-forgotten explosives. I guess every base has their thing. Alert is polar bears, Suffield is bombs.

There’s something morbidly serene about a bright bleached white of old bones against the rich hues of grass and yellow dandelions against a blue sky that tickles my fancy.

I know I just said that Six South has the most craters, however, this crater is in fact in Six North. The remains of bricks are scattered around of whatever structure they decided to blow up here.

***

So where are the birds? Great question.

On the ground.

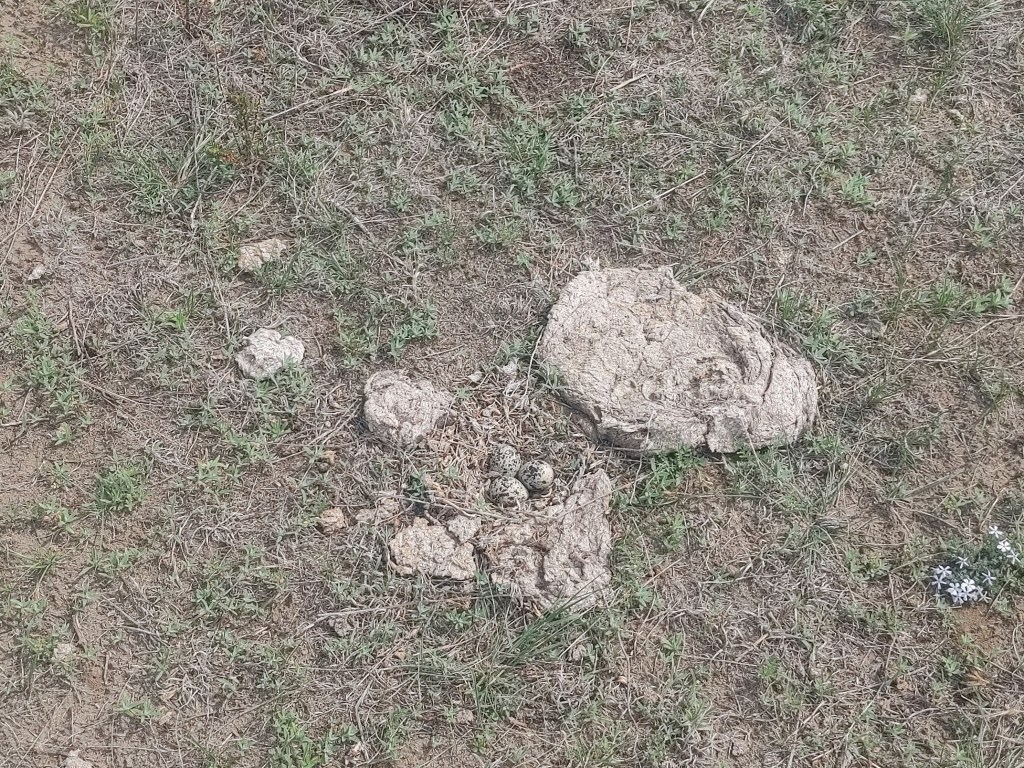

Many grassland birds nest on the ground, and do their best to hide them on the ground. Utilizing anything from the edges of tufts of grass or cacti to cow patties (usually cow patties), birds like the Horned Lark or Chestnut-Collared Longspur will dig small holes and the line it with nest material like dead grass. They blend in incredibly well and can be pretty tricky to find. Luckily, it’s my job to find these hideaways. Most of the time, you can find them by watching the female bring food/nest material, or return to the nest to brood though some species are smarter than others at tricking whoever is watching them (ahem Horned Larks).

Or you can be like a Killdeer and keep it out in the open!

We will be working will two main species this summer by surveying nests, banding chicks and adults, as well as keeping an eye out for previously banded individuals. We will also be attaching radio tags so their migration can be tracked.

Horned Larks [Eremophila alpestris]

Horned Larks are incredibly smart prairie birds that can be found as far as the Canadian arctic tundra up to the southern portion of Ellesmere Island. There is one banded Horned Lark that we saw on the first day that we have nicknamed Gramps, and he is at least 7 years old making him a competitor for the longest lived Horned Lark!

Chestnut-collared Longspur [Calcarius ornatus]

Less bright than the Horned Larks, the Chestnut-collared Longspur is a mascot species for prairies/grasslands and their breeding ranges overlap with that of bison-grazed prairies and fire-burnt grasslands, though, in modern times, they overlap now with cattle-grazed prairies like in Suffield. Despite looking like sparrows, they are coined as ‘longspurs for their long claw on their hind toe (like a cowboys boot!).

Me and Ava banding the chicks of the first Horned Lark nest we found last Wednesday.

***

Some other cool things I’ve seen in the past few days:

There’s two types of cacti native to the plains of Alberta:

- Plains Pricklypear (left)

- Pincushion/Spinystar (right)

The Plains Pricklypear grows in all funky directions, making the larger assortments of it look like a labyrinth from the top down. The Pincushion usually grows in much smaller bunches, and I haven’t seen many get as big as the one in the photo I took. So far, I have not stepped or sat on either of these guys but I feel like it’s an inevitability.

^A cool Blue-bordered Pedunculate Ground Beetle. Also have not sat on one of these and I hope I never do. Look at those pincers.

^Waking up at 4am to get to the base by sunrise definitely has its perks. I usually don’t wake up early enough or really care about the sunrise in average day life, but I think the prairie sunrises have started to change my mind.

^A smokey stormy sky.

The sun breaking through the clouds after a good rain in the field. After being out west for a week, and having a few days out in the field under my belt – including being left alone in the rain with only my binoculars and trail mix for company, I can officially say that I am at home in Medicine Hat and in the grasslands of Suffield 🙂

Leave a comment