On our way back from our fieldwork in Regina, we were invited to stop in to the little town of Indian Head – 45 minutes outside of Regina with a population just under 2,000. Nancy, my boss, has a colleague who was responsible for inviting Nancy and her research to the collaboration project between Living Labs and AgCanada – basically all the farmers field stuff we are doing is for this larger, overarching research study and birds are just a small portion of it.

Indian Head is home to the Indian Head Research Farm most known for its scientific contributions to agriculture research and the distribution of trees too build ‘shelter belts’ to farmers so their soil wouldn’t be blown away by the wind since 1901. It was established in 1887 and unfortunately has been thrown through the ringer with budget cuts, threats to be abolished, and lack of funding. Despite this, it is an amazing scientific and agricultural research hub that when you tour and see first hand what is being studied, it is hard to see why any sane governing body can’t see the integral value it adds to agriculture within Canada if not history of agriculture in Canada. I was impressed to find out that this institute was the first farm to ship grain abroad and is one of the oldest farms in Canada beyond century family farms.

What Are Shelter Belts and Why Are They Important?

Shelter belts, also known as windbreaks, are deliberately planted lines of trees/shrubs/hedges to provide protection to adjacent crops from the wind that can cause soil erosion. They have some other important uses such as keeping snow from drifting onto roadways, providing important habitat to a variety of birds and other animals, and have some very neat interactions with microclimate that I will touch on later. They were incredibly important additions to the farming scene during and after the Dust Bowl at the end of the 1920s that saw drought-effected soil and dirt being scraped away and carried off by incredibly wind storms leaving many farmers destitute. Nowadays, you see shelter belts scattered across the landscape and based on the size of the trees, you may assume many of these are newly planted but on closer inspection you can see a much larger issue. The trees are dying.

One of the first things that Shati, Nancy’s colleague showed us, were the shelterbelts just beyond the main building and barns. Trees in the prairie do not grow as big as the ones you’d see outside of the prairie provinces. Many of them may look young or stunted, but many of the pine belts Shati showed us were over 60 years old. The elements had taken their toll on these trees after decades of being the main wind defense system, and many had begun to lose their needles, branches, and some were dangerously close to falling. In conjunction with the economic situation nation-wide, many farmers, the research farm included, do not have the money to spare to get these shelterbelts safely cut down much less the needed funds to replant. Shati explained that the research farm provided trees for a subsidized cost for years, however, the program had been axed (for lack of better words) recently and now farmers, with trees going for $60-$100 each, are less inclined to rebuild these windbreaks.

Some of the other research being conducted at the research farms was investigating the effects of these tree buffers on crops at different field margins (e.g., how far these trees are from the crop line will effect the field edges in different ways). Too close and the shade that the trees cast can stunt the growth of the crops in their shadow, and too far the trees won’t be able to help the field retain moisture or properly block from the wind (also reducing crop yield), so it’s a delicate balance.

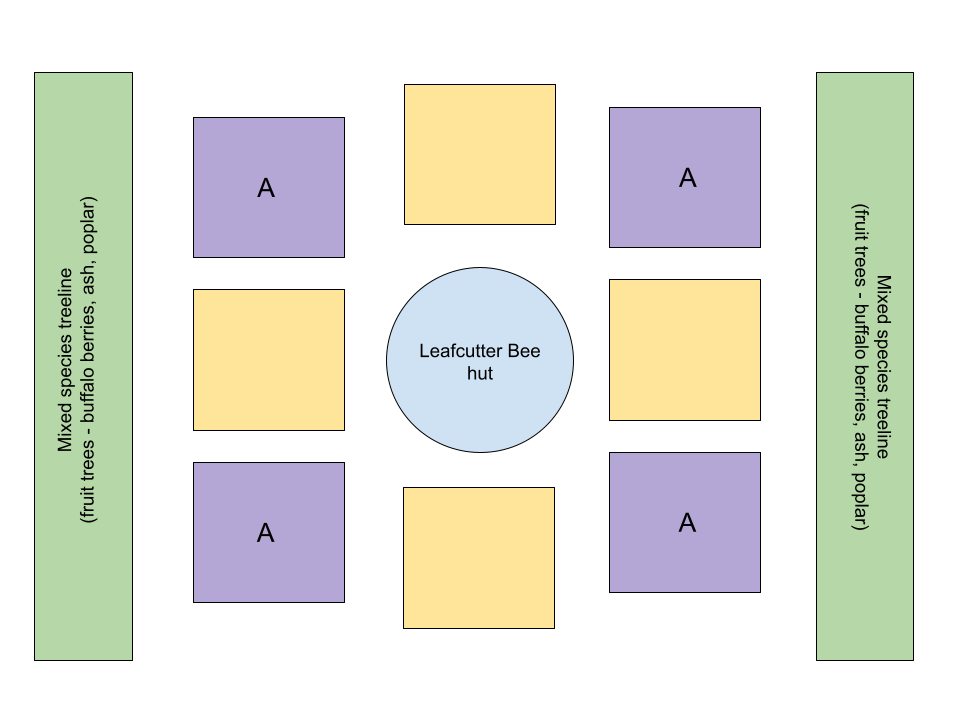

As per my co-op term requirements, and to help my supervisor with the LivingLabs and AgCanada research project, I am writing a literature review report that investigates what impact different crop type has on grassland bird species diversity in the prairie. This, of course, was also being researched at the research farms and we saw a lot of cool experimental plots that investigated small-scale poly-crop (cultivation of multiple plant species in one plot) and intercropping (mix of annual and perennial plants ground at once) and how these plots interact with wildlife. One of the main set ups they have is orchard-style rows of buffalo berry, ash and popular trees separating a checkerboard of alfalfa and other grain with leafcutter bee huts placed strategically in the center. The tree-line provides shelter and maintains a microclimate that increases crop yield as well as provides habitat to birds, insects and other wildlife to pollinate the crops. Alfalfa is a perennial plant that helps with soil health to keep the soil healthy for the other grain grown alongside it, and is pollinated by the leafcutter bees. Leafcutter bees are one of the few native species of bee that can be somewhat easily accommodated for artificially by these huts that house nests made up of small tubing that simulates the underground tunnels leafcutter bees would normally live in. These plots would work best in smaller farmsteads similar to that of the mosaic of farms in Ontario rather than the large expanses out west, however, it provides strong evidence that a diverse mosaic of different habitats is a step in the right direction when it comes to conserving threatened species in the agricultural landscape.

The research farms also has their own tree nursery filled with trees from all over the world, similar to a mini-arboretum. It’s an odd pocket of tree life in a place with barely any trees.

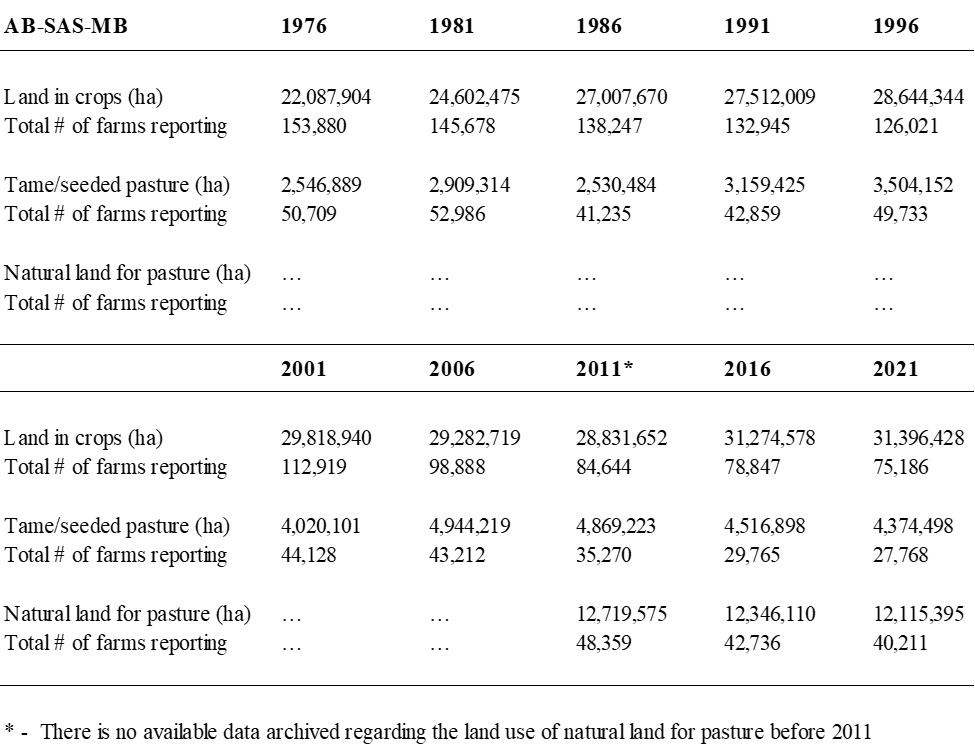

I never expected to get so interested in agriculture, but I think as with most things that stems from a lack of understanding. It’s easy to demonize widespread agriculture as over the last 50+ years, the amount of smaller diverse farmsteads have been decreasing, and amalgamate into large-scale agricultural operations (a fun fact from my research report). Especially when positive change is so hard to see as research incorporating conservation into agriculture is still trying to catch up and reverse the decades of harmful policy (e.g., early 1900s the Canadian government actually paid farmers to convert native prairie to farmland so agriculture kept up with rising population demand, as far as I know, this is no longer the case and has started to become the opposite).

In fact, I remember seeing a co-op posting from the Indian Head Research Farms on the uGuelph co-op job board and thinking, “God, who would want to work there?”. Well, after our tour and subsequent coffee visit with Shati at a very cute cafe/art gallery full of local artists, I do!! there is so much cool stuff being done and even though my report is kind of depressing when you put in perspective how much native prairie is dead and gone, there is hope to implement some really interesting ‘rewilding’ strategies to return some of the native prairie back to farmers fields.

I am currently in Edmonton and have been for the last two weeks (I’ve been getting lazy with the blog), and working at the University of Alberta. I have one week left before I am officially finished my work for the summer. After 8 months of transience, I think I am also officially ready to be back in Ontario and stationary…at least until next summer when my co-op terms start again 😛

Leave a comment